- 「米騒動100年」 ー宇部炭鉱・山口県の米騒動の研究と教育の総合サイトー "100TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE RICE RIOT" ― A COMPREHENSIVE SITE FOR STUDY AND EDUCATION ON THE RICE RIOT IN UBE COAL MINE AND YAMAGUCHI PREFECTURE ―

- サイトマップ site map

- Ⅰ―1 大正7年(1918年)米騒動の全国的展開 《その1》1918年富山米騒動の発生と米騒動研究の今【生徒】(英訳付)Ⅰ. Nationwide development of the rice riots in Taisho7/1918. << Part 1 >> The outbreak of the Toyama rice riots in 1918 and the current state of the rice riots research. 【students】(With English translation )

- Ⅰ―2 《その2》1918年米騒動の全国的展開【生徒】(英訳付)《Part 2》 Nationwide development of the rice riots in 1918 and their significance 【students】(With English translation ) 。 ―NEW― 京都米騒動Kyoto Rice Riots ―NEW― 名古屋米騒動 Nagoya Rice Riots

- Ⅰ―3 《その3》1918年米騒動の歴史的意義【生徒】(英訳付) 《Part 3》 The Historical Significance of the 1918 Rice Riots 【Student】 (with English translation)

- Ⅰ―4 《その4》教科書の米騒動記述の問題点及び陸軍の実弾発射・死亡者に関する教科書・歴史研究者の誤記とメディアの誤報 (英訳付) 《Part 4》 Problems with the descriptions of the rice riots in textbooks, as well as errors by textbooks and history researchers and misreporting by the media regarding the Army's live ammunition firing and the fatalities. (with English translation) 新学習指導要領『歴史総合』(令和4年度・2022年度から)、『日本史探究』(令和5年度・2023年度から)の米騒動の記述について。Regarding the descriptions of the rice riots in the new curriculum guidelines "Modern and Contemporary History" (from academic year 2022) and "Advanced Japanese History" (from academic year 2023). ―NEW― 実教出版の高校日本史探究の教科書の記載に関する緊急連絡(山本作兵衛「ヤマの米騒動」に関して)。Urgent notice regarding the inclusion of Jikkyo Publishing's high school Japanese history textbook (regarding Sakubei Yamamoto's "Yama Rice Riots").

- Ⅱ-1 宇部村(宇部炭鉱)の米騒動と軍隊の発砲【生徒】(英訳付)Ube rice riot and firing of Army 【students】 (With English translation)

- Ⅱ-2 山口県の米騒動【生徒】

- Ⅱ-3 管理者(西岡清美)論文・関連論文。宇部の米騒動研究(史料・文献)。米騒動研究機関・研究会・特集等の紹介

- Ⅱ-4 高校日本史学習指導案(近代・古代・管理者作成)。地域教材開発・教育支援サイト

- Ⅲ―1 「地図で見る宇部地域の発展」原始・古代~近世【生徒】

- Ⅲ―2 「地図で見る幕末の山口県と宇部地域」【生徒】 ―NEW― 幕末を駆け抜けた「草莽」中岡慎太郎

- Ⅲー3 「地図で見る宇部地域の発展」近現代【生徒】

- Ⅲ-4 宇部炭鉱の学習【生徒】

- Ⅳ-1 次期『高等学校学習指導要領』(2018.3.30公表。2022年度実施。「歴史総合」・「日本史探究」)・『地歴科解説』(2018.7.17公表)

- Ⅳ―2 教育課程(カリキュラム)全般。中・四国、九州の一部普通科高校教育課程と出身者例 ―NEW―令和6年度中国・四国、九州高校教育課程例・令和6年進路実績例(中間)。 山口県立宇部西高校募集停止問題

- Ⅳ―3 大学入試・大学入学共通テスト日本史関連【史料問題・生徒】 2019~2023センター試験・共通テスト日本史B史料問題過去問解説。令和5年共通テスト本試験(2023.1.14実施)日本史B分析。令和7年度以降の共通テスト(新学習指導要領による入試・『歴史総合・日本史探究』)に向けて(2022.11.9公表「試作問題」分析) ―NEW― 令和6年度大学入学共通テスト本試験日本史B問題の分析と史料問題解説(2024.1.13実施)

- プロフィール・コメント(Comment)

Ⅰ 大正7年(1918)米騒動の全国的展開(生徒)Nationwide development of the rice riots in Taisho7/1918 (students)

1918年米騒動は、シベリア出兵を契機とした米価高騰に伴い、7月に富山県で発生し、8月10日から京都、名古屋の大都市で大規模な米騒動へ発展し、軍隊が出動して鎮圧する事態となりました。8月17日からは山口県の宇部炭鉱と福岡県の峰地炭鉱で鉱夫の労働争議が米騒動に発展し、9月12日に福岡県三池炭鉱の米騒動が終息するまで続きました。

米騒動の発生時期、参加人数、発生道府県には諸説があります。また米騒動をどのように認識するかの議論が続いています。

The rice riots of 1918 occurred in Toyama Prefecture in July due to the rise in rice prices triggered by the Siberian intervention, and from August 10th, it developed into large-scale rice riots in the big cities of Kyoto and Nagoya, and it became a situation that the army was dispatched to suppress it. From August 17, the labor dispute between miners at the Ube Coal Mine in Yamaguchi Prefecture and the Mineji Coal Mine in Fukuoka Prefecture developed into the rice riots, which continued until the rice riot at the Miike Coal Mine in Fukuoka Prefecture ended on September 12.

There are various theories about when the rice riots occurred, the number of participants, and the prefectures where they occurred. There is also ongoing debate on how to recognize the rice riots.

Ⅰ―1《その1》1918年富山米騒動の発生と米騒動研究の今<< Part 1 >> The outbreak of the Toyama rice riots in 1918 and the current state of the rice riots research

(1)米騒動の背景 (1) Background of the Rice Riots

グラフから、大戦景気による物価騰貴に対し実質賃金が上昇していなかったことが米騒動の背景にあったことが読み取れます。すなわち、第一次大戦による空前の好景気で、国民所得がほぼ倍増したものの、所得の分配に偏りがあり、企業経営者・株主・地主・米穀商等と勤労者の間の経済格差が拡大しました。政府が米価政策に失敗したことも加わり、シベリア出兵の決定過程をきっかけに米価の暴騰が始まると、経済格差の矛盾が顕在化しました。すなわち、富裕層や自給米のある農家などを除き、ほとんどの勤労者が、まじめに働いてもその日の白米が購入できないという社会問題となったのです。まじめに働いている人が、家族に食わせ、生きていくために米屋を襲撃するしかない状況が生み出されました。襲撃は米を掠奪するのではありません。暴徒は、米屋が不当な利益を上げていることに対する社会的制裁として、米の廉売要求、店舗の破壊、米のまき散らしなどを行いました。経済格差の大きかった経済の先進地から米騒動がはじまり、米屋だけでなく大商店や富豪も襲撃されました。

From the graph, it can be seen that the background of the rice riots was that real wages did not rise against the rise in prices due to the economic boom of World War 1. In other words, due to the unprecedented economic boom of World War I, although national income almost doubled, income distribution is biased, and the economic disparity between business owners, shareholders, landowners, rice dealers, etc. and workers widens. With the failure of the government's rice price policy, the contradiction of economic disparity became apparent when the rice price surge began in the wake of the decision process for sending troops to Siberia. In other words, it became a social problem that most workers, except for wealthy people and farmers with self-sufficient rice, could not buy white rice for the day even if they worked diligently. A situation was created in which serious workers had no choice but to attack the rice shop in order to feed their families and survive. The assault is not an act of looting rice from a rice shop. The mob has made social sanctions against rice stores making unfair profits, such as demanding bargain sales of rice, destroying stores, and sprinkling rice etc. The rice riots began in the advanced areas of the economy, where economic disparities were large, and not only rice shops but also large shops and millionaires were attacked.

純利益の増大と賃金の抑制 Increasing net income and curbing wages

管理者がエクセルで筆写して作成した画像。An image created by the administrator in Excel.

表は、大企業の例であるが、大戦景気で所得は増大したが、増大分は企業所得(利潤)に分配され、雇用者所得(職工賃金)が抑圧されている。労働者は、物価上昇に対し残業で生活を支えていた。この結果、株主の配当や経営者の賞与が厖大になった反面、賃金は物価の上昇に追いつかずに経済格差が拡がった。米価暴騰の局面でこの矛盾が露呈し、富裕層は栄耀栄華な生活を送り、職工(工場労働者)は生活ができなくなってストライキが発生した。

「生活にわずかな潤いをもたらした賃金の上昇も、利潤の増加率と比べると問題にならないほど小さく、大戦期の好景気を肌で感じとっていた労働者にとって、さきの労働者としての自覚は正当な分配の要求=賃金に対する権利意識に発展する契機を内包していた」。一方、「大戦期の労働者数の急速な膨張は経営の労働力統轄体制を弛緩せしめ、資本の労働支配にさまざまな亀裂を生じさせることになった」。「労働者の権利意識の伸長と労働力統轄体制の弛緩は、労働争議の頻発となって現れた」。(西成田153頁)

The table shows an example of a large company. Although income increased during the war economic boom, the increase was distributed to corporate income (profit) and employee income (work wages) was suppressed. Workers supported their lives by working overtime in response to rising prices. As a result, while dividends from shareholders and bonuses from managers have become enormous, wages have not caught up with rising prices and the economic disparity has widened. This contradiction was revealed in the phase of the rice price surge, the wealthy people lived a glorious life, and the craftsmen (factory workers) could not live and strikes occurred.

"The rise in wages, which brought a little bit of gain to our lives, was also small enough to be insignificant compared to the rate of increase in profits. For workers who felt the boom of the war period, their awareness as a worker had contained an opportunity to develop into a demand for legitimate distribution = a sense of rights to wages." On the other hand, "the rapid expansion of the number of workers during the World War period loosened the labor force control system of management and caused various cracks in the labor control of capital." "The growing awareness of workers' rights and the relaxation of the labor force control system have manifested themselves in frequent labor disputes." (Nishinarita, p. 153)

《関連》政府の米価政策 『米騒動の研究』第1巻 17~39頁。138~145頁

米価の安定と需給関係の調整のため、政府は、暴利取締令(1917.8.30)と外米(東南アジア米)管理令(1918.4.25)を出した。また、朝鮮米移入と期米市場(先物取引)の抑圧も行った。シベリア出兵決定時(1918.7.17)には在米調査(10石以上の内地米を所有する地主・米商の調査)の通牒も実施した。しかし、米の需給関係と米価上昇は改善しなかった。米騒動発生後、内地米を強制買収する米穀収用令(1918.8.16)、外米管理令改正(同日)、収用価格公定政策により正米相場(しょうまいそうば・現物取引)は下落した。

米騒動発生後の政策により米価の高騰は止まり、富豪の寄付金を中心にして市場価格(内地米40~45銭、外米20銭程度)より安く売られた。(一般的に、内地米白米1升25銭、外米白米1升15銭に値下げされた)。賃金値上げにより、勤労者の生活は落ち着きを取り戻し、米騒動は終息に向かった。

《補足》

〇「暴利取締令」

市場価格の変動を誘発し、利益を得るために、買占めや売惜しみを警告する法令です。この法令は、1米穀類、2鉄類、3石炭、4綿糸・綿布、5紙類、6染料、7薬品の七品目に適用されたしかし、一般物価や米価の上昇は根本的な原因があるために起こっており(後述)、買占めはそれを助長しているだけでした。すなわち、米価高騰の根本的原因を解決しないまま、買占めを取り締るだけでは米価の高騰を抑えることはできなかった。

〇「外米管理令」

政府は外米輸入の促進のために有効とみられた関税引下げや運賃引き下げはせず、外米管理規則を公布した。外国米の輸入、朝鮮米・台湾米の移入、買入・売渡を三井物産、鈴木商店、湯浅商店、岩井商店など7社を指定して、指定価格や買入条件を定めて取扱わせるものである。政商が巨利を得て損をしないように政府が保証して外米の輸入をはかったもので、内地米価引き下げと供給増加のいずれにも失敗した法令である。

<< Related >> Government's rice price policy, "Study of the Rice Riots," Volume 1, pp. 17-39. Pages 138-145

In order to stabilize rice prices and adjust the supply-demand relationship, the government issued unjustified profit control order (1917.8.30) and a foreign rice (Southeast Asian rice) management order (1918.4.25). It also brought Korean-rice and suppressed the rice futures trading market. In addition, when the Siberian intervention was decided (1918.7.17), and the government has decided the noticing of survey of the owned rice (survey of landlords and rice merchants who own 1500 ㎏ or more mainland rice). However, the supply-demand relationship and the rise in rice prices did not improve. After the rice riots, the spot market's rice price (shomai-soba / spot transaction) fell due to the rice expropriation order (1918.8.16) for forcibly acquiring mainland rice, the revision of the foreign rice management order (same day), and the official expropriation price policy.

The rise in rice prices stopped due to the policy after the rice riots, and rice was sold cheaper than the market price (inland rice 40-45 sen, foreign rice 20 sen) centered on donations from millionaires. (In general, the price was reduced to about 25 sen for mainland white rice and 15 sen for foreign white rice). In addition, wages have been raised, workers' lives have calmed down, and the rice riots have come to an end.

"supplement"

“Unjustified Profit Control Order”

It is a decree that warns against hoarding and being reluctant to sell in order to induce fluctuations in market prices and obtain profits. This decree was applied to seven items: (1) rice, (2) iron, (3) coal, (4) cotton thread / cotton cloth, (5) paper, (6) dyes, and (7) chemicals.

However, the rise in general prices and rice prices was caused by the root cause (described later), and the hoarding only helped it. In other words, it was not possible to curb the rise in rice prices simply by cracking down on hoarding without resolving the root cause of the rise in rice prices.

"Foreign Rice Management Order"

The government did not reduce tariffs or freight rates, which seemed to be effective in promoting foreign rice imports, but promulgated foreign rice control rules. Import of foreign rice / transport Korean rice and Taiwan rice of to mainland / purchase / sale is handled by designating 7 companies such as Mitsui & Co., Suzuki Shoten, Yuasa Shoten, and Iwai Shoten, and setting designated prices and purchase conditions. It is a decree in which the government guarantees that political entrepreneurs do not lose huge profits and imports foreign rice, and it fails in both the reduction of the price of mainland's rice and the increase of supply.

《資料》東京・大阪・神戸の内地白米販売価格 << Document >> Mainland white rice selling price in Tokyo, Osaka, and Kobe. (Medium level mainland white rice. Per 1Koku (150 kg). Unit / yen)

表は管理者が『米騒動の研究』を筆写(エクセル)した画像。The table is an image of the administrator copying (Excel) "Study of the Rice Riots".

米価は、米騒動前年の1917年4月までは諸物価上昇の中で安定していた。ところが、1917年の5月~7月にかけて高騰した(東京2.7割、大阪4.4割、神戸3.5割の上昇。7月と4月の比較)。この原因は大戦景気による、通貨膨張、一般物価高、米の生産費高がありました。また、需要の増大と供給の減少の原因は、工業・商業の発展による都市人口の増加、農家の自家消費の増加、農家の養蚕業拡大による米作離れ、外米及び植民地米の輸入・移入不足でした。これらが米価高騰の根本的な原因です。ただし、急激な輸入・移入増は東南アジアや植民地(朝鮮・台湾)の経済を混乱させることに繋がります。

米価上昇局面では、端境期の上昇を見越して、所有米を持つ地主が米を売り惜しむため、さらに供給量が不足して米価が高騰しました。

「ストライキ運動飛躍の年」である1917年の炭鉱の労働争議は全国で16件発生している。そのうち15件が同年7月~9月に発生しており(荻野喜弘『筑豊炭鉱労資関係史』201頁)、米価高騰が賃上げ要求のストライキに繋がったことがわかる。

米価上昇の局面で、政府は地主(政友会の基盤)・政商を優遇するため、有効な米価対策を執らなかった。米価高騰の根本原因が放置されたまま、1918年の端境期(富山県では鍋割月(なべわれづき。7・8月)と呼ばれていた)の夏が再来した。7月にシベリア出兵が報道されると、米価維持のための政策や需給関係を放置したことによる矛盾が顕在化した。8月2日のシベリア出兵宣言を契機に米価はさらに奔騰した。(東京3.2割。神戸4.5割。8月と6月の比較)。

シベリア出兵の兵糧米の確保は米の需給関係に影響を与える量ではなかった。1918年の日本の人口5566万人に対し、出兵の総数は7万3千人に過ぎない。また、兵士がシベリアで米を食べても日本で食べても米の消費量に大きな差はない。したがってシベリア出兵により米の需要が大きく増えたということはない。

米価高騰には根本的な原因があり、シベリア出兵が米価高騰の原因ではない。しかし、シベリア出兵を契機に、米の買い占め、売り惜しみが発生して、米価が暴騰した。1917年には発生しなかった米騒動が、なぜ1918年夏に発生し、全国に拡大したのだろうか。世論や新聞はシベリア出兵に反対していた。シベリア出兵と米騒動の関係は今後の課題としたい。

While prices were rising, rice prices were stable until April 1917, the year before the rice riots. However, it soared from May to July 1917. (Tokyo 27%, Osaka 44%, Kobe 35% rising. Comparison between July and April). The causes of this were expansion of currency, high general prices, and high rice production costs due to the war boom. In addition, the causes of increased demand and supply shortage of rice include an increase in urban population due to industrial and commercial development, an increase in self-consumption by farmers, a departure from rice cultivation due to the expansion of sericulture by farmers, a shortage of foreign rice imports and colonies rice's transport to mainland. These were the root causes of the soaring rice prices. However, a rapid increase of imported rice and of transport colonies rice to mainland will lead to disruption of the economies of Southeast Asia and colonies (Korea and Taiwan).

In the phase of rising rice prices, landowners who own rice in anticipation of a rise in the off‐crop season will be reluctant to sell rice, resulting in a further shortage of supply and soaring rice prices.

There were 16 coal miner labor disputes nationwide in 1917, the "year of the leap forward in the strike movement." Fifteen of them occurred from July to September of the same year (Yoshihiro Ogino, "History of Chikuho Coal Mine Labor Relations", p. 201), and it can be seen that soaring rice prices led to a strike demanding a wage increase.

In the phase of rising rice prices, the government did not take effective rice price measures in order to give preferential treatment to landowners (the foundation of the Seiyukai) and political entrepreneurs. The summer of the off‐crop season of 1918 (known in Toyama Prefecture as Nabewarezuki (July / August)) has returned, leaving the root cause of the soaring rice prices untouched. When the Siberian intervention was reported in July, a contradiction became apparent due to neglecting policies to maintain rice prices and adjustments to supply and demand. The price of rice rose further with the declaration of Siberian intervention on August 2. (Tokyo 32%, Kobe 45% rising. Comparison between August and June).

Securing rice for Siberian intervention was not an amount that affected the supply-demand relationship of rice. The total number of troops dispatched was only 73,000, compared to Japan's population of 55.66 million in 1918. Also, there is no big difference in rice consumption between soldiers eating rice in Siberia and Japan. Therefore, the demand for rice has not increased significantly due to the Siberian intervention.

There is a root cause for soaring rice prices, and Siberian intervention is not the cause for soaring rice prices. However, when the government decided to send troops to Siberia, the price of rice soared due to the hoarding and being reluctant to sell. Why did the rice riots that did not occur in 1917 occur in the summer of 1918 and spread nationwide? Public opinion and newspapers opposed the Siberian intervention. The relationship between Siberian intervention and the rice riots is an issue for the future.

(2)1918年(大正7)米騒動はじまる。(2) 1918 (Taisho 7) The rice riots begin.

〇1918年(大正7)富山米騒動のはじまり。定説・・魚津町7月23日(2018年7月23日が100年目でした。)〇 1918 (Taisho 7) The beginning of the Toyama rice riot. The established theory ... July 23, Uozu Town (July 23, 2018 was the 100th year)

1918年(大正7)7月23日、女性荷役労働者数十名が魚津町大町(現魚津市)の旧十二銀行米倉前に押しかけ、米の移出を阻止した。これが近代最大の民衆行動である米騒動の始まりとされている。しかし。近年は、魚津町を含む東部富山湾沿岸都市群を初期発生地とする説が有力である。

On July 23, 1918 (Taisho 7), dozens of female cargo handling workers rushed to front of the former Twelve Bank rice storehouse in Omachi, Uozu Town (currently Uozu City) to prevent the transport to another part of the country of rice. This is said to be the beginning of the rice riots, which is the largest people's action in modern times. However, in recent years, the theory that the eastern Toyama Bay coastal cities including Uozu Town is the initial region of occurrence is predominant.

「米騒動発端の地見取図」。修復された旧十二銀行米倉前の説明版の一部を拡大した画像。

女性荷役労働者ら数十名が米倉前に押しかけ、「女房達代表」が「洄漕店番頭」と交渉した状況が図示されている。女性たちは米俵が伊吹丸に運ばれて北海道に移出するのを阻止した。米蔵前の道路そばに「米騒動発祥の地」の石碑が建てられている。

"A sketch of the initial place of occurrence of the rice riots". An enlarged image of a part of the explanation version of the restored former Twelve Bank rice storehouse.

The figure shows a situation in which dozens of female cargo-handling workers rushed in front of rice storehouse, and the "wife's representative" negotiated with the "shipping agent's clerk." The women prevented the straw rice bags from being carried to the Ibuki Maru and then transporting to Hokkaido. A stone monument of "the birthplace of the rice riot" is erected near the road in front of the rice storehouse.

「うおづ散歩」の説明板の左上の写真は、女性荷役労働者(説明版では「女仲仕」と記載)が米倉から米俵(1俵60㎏)を背負い、はしけ(小舟)に積み込んでいるところです。陸上の仲士を陸仲仕(おかなかし)といいます。説明版の左下の写真は、米俵をはしけで伊吹丸に運んでいるところです。海上の仲仕を沖仲仕(おきなかし)といいます(現在は、「仲仕」に職業差別の意味があるため使わず、港湾労働者といいます)。伊吹丸は米俵を積み込んで北海道に移出するため沖合に停泊していました。女性荷役労働者の夫の多くは、漁船・船舶労働者で出稼ぎ中でした。家庭を守る女性荷役労働者は米価高騰で米の購入が困難になっているにもかかわらず、米俵が移出されることに抗議し、移出を阻止しました。

In the upper left photo of the explanation board for "Uozu Walk", female cargo-handling workers (described as "female Nakashi" in the explanation version) carries a straw rice bag (60 kg per bag) from rice storehouse and loads a rice bag into a hashike (small boat). A land-based cargo handling workers is called "Oka-Nakashi". The photo at the bottom left of the explanatory version shows a hashike carrying the straw rice bags to Ibuki-Maru. The cargo-handling worker on the sea is called "Oki-Nakashi". (Currently, "Nakashi" has the meaning of occupational discrimination, so it is not used and is called a dock worker). Ibuki-Maru was moored offshore in order to load the rice bags, and transport them to Hokkaido. Many of the female cargo-handling workers' husbands were working away from home on fishing boats and ships. Since the soaring prices of rice made it difficult to buy rice, female cargo workers who protect their families protested the transport to another part of the country of straw rice bags and prevented the transport to another area of them.

《参考》横山源之助顕彰碑 << Reference >> Yokoyama Gennosuke Honoring Monument

前記の説明版や米騒動のモニュメントのある大町海岸公園の一角に、魚津町出身の横山源之助の顕彰碑が建てられている。横山源之助は、「明治期における二つの労働報告の古典、『日本の下層社会』のみならず『職工事情』の創出にもかかわっていた」ことで知られている(岩波文庫『日本の下層社会』404頁)。『職工事情』がもととなって日本最初の工場労働者(職工)保護立法である「工場法」が制定された。(「工場法」(1911年公布。1916施行。1947年「労働基準法」施行により工場法廃止))。横山の業績は、日本資本主義成立期の工場労働者実態調査と工場労働者保護に貢献したことである。(「工場法」に対応する炭鉱・金属鉱山などの鉱業労働者保護法令は「鉱夫労役扶助規則」(1916年施行)である)。

顕彰碑には、前記の評価とは別に、「社会福祉の先覚」としての横山の業績の説明版が付設されている。横山は、明治期の米騒動を契機として始まった魚津町の社会福祉制度に注目していたことが分かる。

魚津町は大正7年米騒動の「発祥地」となり、米騒動を契機に全国で社会政策(民生委員制度の先駆となる方面委員制度など)が始まった。魚津町は大正7年米騒動だけでなく、横山が注目したように、大正7年米騒動以前に社会政策(初期の「生活保護」制度(1889貧民救助規定・1890貧民救助法))が実施された。魚津町は、社会政策でも「発祥地」の位置を占めている。

A memorial monument to Yokoyama Gennosuke from Uozu Town is built in a corner of Omachi Kaigan Park, where the above explanation version and the monument of the rice riots are located. Yokoyama Gennosuke is known for being involved in the creation of "Factory worker information" as well as "the lower society of Japan," which is a classic of two labor reports in the Meiji era. (Iwanami Bunko, "the lower society of Japan," p. 404). The "Factory Law" was enacted, which is the first legislation to protect factory workers in Japan, based on "Factory worker information". ("Factory Law" (promulgated in 1911. Enforced in 1916. The Factory Law was abolished by the enforcement of the "Labor Standards Law" in 1947). Yokoyama's achievements contributed to the fact-finding survey of factory workers and the protection of factory workers during the period when Japanese capitalism was established. (The Mining Worker Protection Law for coal mines and metal mines that corresponds to the "Factory Law" is the "Mining Worker's Work Assistance Regulations" (enforced in 1916)).

In addition to the above evaluation, the Honoring Monument is accompanied by an explanatory version of Yokoyama's achievements as a "forerunner to social welfare." It can be seen that Yokoyama was paying attention to the social welfare system of Uozu Town, which started in the wake of the rice riot in the Meiji era.

Uozu Town became the "birthplace" of the rice riots of 1918, and social policies began nationwide in the wake of the rice riots (such as the area committee system that pioneered the civil welfare committee system). In Uozu Town, not only the rice riots of 1918, but as Yokoyama noted, social policies (initial "life protection" system (1889 poor people's rescue regulations, 1890 poor people's rescue law)) were implemented before the rice riots of 1918. Uozu Town occupies also the position of "birthplace" in social policy.

「下層社会」とは What is "lower society"?

「下層社会」に関して、金澤敏子・向井嘉之・阿部不二子・瀬谷 實『米騒動とジャーナリズム 大正の米騒動から百年』2016年、梧桐書院、9~10頁を引用します。

「当時の下層社会では、まず定職を持っている低所得層を「細民」(さいみん)と呼び、定職なく日雇いなどで生活する層を「貧民」(ひんみん)、そして生活保護を要する最も貧しい人達を「窮民」(きゅうみん)と呼んだ。隅谷三喜男(すみやみきお)の説明を付け加える。「細民」は、定職があるだけ生活が安定しており、その中核をなすものは職人である。「細民」と区別される「貧民」は一般的には大小の貧民窟に居住し、人力車夫と職人の手伝い、その他の日雇労働者、すなわち不熟練の筋肉労働者です。その生活は家族労働によって辛うじて維持される程度である。「窮民」は、いわば貧民の最下層、極貧(ごくひん)者で救恤(きゅうじゅつ:困っている人を助けるの意)の対象となる(隅谷三喜男『日本賃労働史論』1995、東京大学出版会)。隅谷の分類は當時貧民=下等社会と呼ばれたものを、明治期東京府下の実情を背景に、社会的には明確に異なる三つの社会として分析している。(中略)特に「細民」と「貧民」の区別については、「貧民が貧富という生活基盤によって、したがってそれによって規定される生活様式の相違によって区別されるのに対し、細民は賤民であって、貴賤上下という身分的差別にもちいた概念である。したがって細民は必ずしも貧民と対立する概念ではなかったし、またしばしば同一視してもちいられている(隅谷前掲書)」ので、新聞記事では包括的に下層社会として考えたほうが良い時が多い。」

Regarding "lower society", I quote Kanazawa Toshiko, Mukai Yoshiyuki, Abe Fujiko, Setani Minoru, "Rice riot and journalism, 100 years from the rice riot of the Taisho era," 2016, Goto Shoin, pp. 9-10.

"In the lower society at that time, the low-income group who had a regular job was called the" Saimin", the group who had a day laborer without a regular job was called the" Hinmin", and the poorest people who needed livelihood protection were called the" Kyumin". Add an explanation of Sumiya Mikio. The life of a "Saimin" is stable as long as there is a regular job, and the core of it is a craftsman. The "Hinmin", distinguished from the "Saimin," are generally rickshawmen, craftsmen's helpers, and other day laborers who live in large and small slums, and they are unskilled muscular workers. Its life is barely maintained by family labor. The "Kyumin" is, so to speak, the lowest layer of the poor, the extremely poor, and is the target of relief. (Sumiya Mikio, "History of Japanese Wages and Labor" 1995, University of Tokyo Press). Sumiya's classification analyzes what was called the poor people = lower society at the time as three societies that are clearly different from each other in the context of the actual situation in Tokyo prefecture during the Meiji era. (Omitted) In particular, regarding the distinction between "Saimin" and "Hinmin," "Hinmin are distinguished by the living foundation of the rich and the poor, and therefore by the difference in the lifestyle defined by it, whereas the Saimin are Senmin(humble people), and it is a concept based on the identification of the discrimination by the identity or social status. Therefore, the Saimin were not necessarily the concept of confrontation with the Hinmin, and they are often equated with each other (Sumiya, op. Cit.), So it is often better to think of them as a comprehensive lower society in newspaper articles. "

2022.1.8更新 2022.1.8 update

〇大正7年富山米騒動を全国的騒擾とせず・・吉河光貞『所謂米騒動事件の研究』〇The rice riots of Toyama in 1918 are not a national riot ... Mitsusada Yoshikawa "Study of the so-called Rice Riots Incident"

検事吉河光貞は大正7年米騒動を研究し、昭和14年に『所謂米騒動事件の研究』を著しました。

このなかで、大正7年富山米騒動を「富山縣は騒擾発生せざりしも、同縣は所謂米騒動の發端地なるを以て便宜同縣下の哀願運動を騒擾に準じて記載した」(前掲書102頁表)としました。大正7年富山米騒動は、起訴(騒擾罪など)がなく刑事事件化していませんので吉河は騒擾が発生しなかったと認識しました。

吉河は、司法省の検事の立場から、犯罪研究の対象として米騒動を調査・分析したので、犯罪(騒擾罪などの刑事事件)として起訴されていない大正7年富山米騒動を「米騒動」・「米騒擾」と認識しなかったのです。一方、『米騒動の研究』は米価引き下げ・(引き下げ資金としての)寄付金などを米商、富豪、警察・行政当局に要求する街頭の民衆行動を「米騒動」としていますので、大正7年米騒動の出発点を富山米騒動としています。

吉河は、富山県には、7、8月の「鍋割月(なべわれづき)」に発生する「傳統的風習」の哀願行動があり(前掲書200~205頁表)、一揆または騒動の程度に及ばないものとしています(前掲書200頁)。吉川は、富山県で発生したのは哀願行動であり、起訴がないので騒擾事件ではないが、「所謂(いわゆる)」米騒動の発端地なので便宜上騒擾に準じて記載したと述べています。

吉河は全国的騒擾を8月10日の京都・名古屋両市の騒擾から9月17日の福岡県嘉穂郡頴田(かいた)村の明治炭鉱第2坑の労働争議までの39日間としています(吉河前掲94頁)。

これに対し、『米騒動の研究』(第5巻「はじめに」)は、吉河が明治炭坑の労働争議を米騒動終期とした説を批判しました。吉河が検事の立場から明治炭坑の労働争議が治安警察法違反の刑事事件となったために米騒動の終期としていることを疑問視しました。 「米騒動を街頭の騒動として、民衆の行動形態に即してとらえるべき」であるとし、大正7年富山米騒動を大正7年米騒動の先駆と位置づけ、街頭の騒動化しなかった明治炭坑の労働争議を米騒動から除外しました。このことから、『米騒動の研究』は、大正7年の米騒動は7月22日(7月23日)に富山県魚津町ではじまり、熊本県万田(まんだ)坑で9月12日に終息したと考えています。(『米騒動の研究』第5巻6頁。万田坑は、福岡県・熊本県にまたがる三井三池炭鉱(数坑あった)の一つで、熊本県玉名郡荒尾(あらお)村にあった。)

管理者は、『米騒動の研究』と同様、米価高騰に伴う街頭の騒動が発生した大正7年富山米騒動を大正7年米騒動のはじまりとします。

近年、井本三夫の聞き取り調査、研究により大正7年富山米騒動が始まった時期は再検討が行われています。また、井本は、米価高騰と賃上げを求める広義の米騒動は大正6年(1917)からはじまったとする見解を発表しており、今後の課題となっています。

米価高騰がピークに達した8月10日に京都市と名古屋市で大規模な米騒動が発生します。米価高騰が社会問題となり政府は米価の廉売政策を実施するとともに軍隊を出動して鎮圧しました。管理者は、米価高騰で生活が破壊された民衆の起こした大都市の米騒動は、8月16日の東京市の騒動を終期として収束すると考えます(米騒動前期)。

8月17日に山口県の宇部炭鉱と福岡県の峰地炭鉱で賃金値上げを要求する労働争議が騒動化しました。宇部村では賃上げの低額回答に反発した鉱夫が炭鉱組合事務所や経営者宅だけでなく、労資関係と直接結びつかない市街地の富豪、商店、遊郭などを襲撃しました。また、翌18日には、鉱夫らは、警察に連行された仲間の釈放を求めて警察分署に押し出し、軍隊が発砲して13名の死者がでました。この米騒動は、8月16日までの米騒動と性格や展開に相違がみられます。管理者は8月17日の宇部米騒動から9月12日の万田坑米騒動までを「米騒動後期」とします。

ただし、米騒動の性格の分析と前期・後期の時期区分に関する研究は今後の課題とします。

大正7年米騒動は、教科書に記載されてよく知られている富山県の「越中女房一揆(越中女一揆)」ですべてが語れる歴史的事象ではありません。以下で述べるように、米騒動の発生時期や性格について、現在も研究や議論が続いています。

Prosecutor Yoshikawa Mitsusada studied the rice riots of 1918 and wrote "Study of the so-called Rice Riots Incident" in 1945.

Among them, the Toyama rice riots in 1918 was described as "Toyama riots did not occur, but since it was the place where the so-called rice riot started, for convenience, Toyama's the appeal movement is described the same treatment as the riot. "(Table on page 102 of the above-mentioned book). In 1918, Toyama rice riots was not prosecuted (such as the crimes of disturbance) and was not a criminal case, so Yoshikawa recognized that the riot did not occur.

From the standpoint of a prosecutor of the Ministry of Justice, Yoshikawa investigated and analyzed the rice riots as a subject of criminal research. For this reason, Yoshikawa did not recognize the rice riots of Toyama in 1918, which had not been charged as a criminal case, as "rice riot" or "rice disturbance." On the other hand, "Study of the Rice Riots" recognizes the street people's behavior that demands rice price cuts and donations (as funds for the cut) for rice merchants, millionaires, police and administrative authorities as "rice riots". For this reason, "Study of the Rice Riots" recognizes that the starting point of the rice riot in 1918 is the Toyama rice riots.

Yoshikawa pointed out that Toyama Prefecture has the appeal movement of "traditional customs" that occurs in "Nabewarezuki" in July and August (see the above-mentioned table on pages 200-205), he recognized that it has not reached the level of ikki or riot (op. Cit., P. 200). Yoshikawa believes that what happened in Toyama Prefecture was a pleading act, not a disturbance case because there was no prosecution. However, because Toyama is the place where the "so-called rice riot" started, he states that Toyama's the appeal movement is described the same treatment as the rice riot for convenience.

Yoshikawa thinks that the nationwide riots lasted 39 days from the riots in Kyoto and Nagoya on August 10 to the labor dispute at the second mine of the Meiji coal mine in Kaita Village, Kaho District, Fukuoka Prefecture on September 17 (Yoshikawa, supra, p. 94).

In response, "Study of the Rice Riot" (Volume 5, "Introduction") criticized Yoshikawa's theory that the labor dispute at the Meiji coal mine was the end of the rice riot. "Study of the Rice Riot" questioned that Yoshikawa, from the prosecutor's point of view, ended the rice riot because the labor dispute at the Meiji coal mine became a criminal case that violated the Security Police Act. "Study of the rice riot" states that "the rice riot should be regarded as a street riot and should be grasped according to the behavior of the people", and the Toyama rice riot in 1918 was positioned as a pioneering to the rice riot in 1918. And the labor dispute of the Meiji coal mine, which had no street riot, was excluded from the rice riot. For this reason, "Study of Rice Riot" describes that the rice riot in 1918 started on July 22 (July 23) in Uozu Town, Toyama Prefecture, and ended on September 12 at the Manda Coal Pit in Kumamoto Prefecture. ("Study of Rice Riot", Vol. 5, p. 6). The Manda Coal Pit is one of the Mitsui Miike coal mines (there were several mine) that straddles Fukuoka and Kumamoto prefectures, and was located in Arao village, Tamana district, Kumamoto prefecture.

Similar to "Study of rice riots", the administrator considers the rice riots of Toyama in 1918, which caused the riots on the streets due to the soaring rice prices, to be the beginning of the rice riots of 1918.

In recent years, research of interviews and study by Imoto Mitsuo have reexamined the period when the Toyama rice riots began in 1918. In addition, Imoto has announced the view that the rice riots in the broad sense of demanding soaring rice prices and wage increases began in 1917, which is an issue for the future.

On August 10, when the rise in rice prices peaked, a large-scale rice riot broke out in Kyoto and Nagoya. The soaring rice prices became a social problem, and the government implemented a bargain price policy for rice and dispatched an army to suppress the rice riots. Administrator thinks that the rice riots in big cities, whose lives had been destroyed by soaring rice prices, ended with the riots in Tokyo on August 16th. The administrator thinks this period the "first half of the rice riots."

On August 17, a labor dispute the Ube Coal Mine in Yamaguchi Prefecture and the Mineji Coal Mine in Fukuoka Prefecture, which demanded a wage increase, developed into the riots. In Ube Village, miners who opposed the low wage increase attacked not only coal miners' union offices and managers' homes, but also millionaires, shops, and Yukaku etc. in urban areas that are not directly linked to labor relations. On the following day, the 18th, the miners pushed out to the front of police branch office in search of the release of their companions taken by the police, and the army fired, killing 13 people. This rice riots are different from the rice riots until August 16 in nature and development. The administrator thinks the period from the Ube rice riot on August 17 to the rice riot at Manda coal pit on September 12 as the "late rice riots".

However, analysis of the characteristics of the rice riots and research on the division of the early and late stages are left as future tasks.

The rice riots of 1918 are not a historical event that can be fully explained in the well-known "Ecchyu Nyoubou Ikki" in Toyama Prefecture, which is described in textbooks. As described below, research and discussions are still ongoing on the timing and nature of the rice riot.

〇「米騒動」・「米騒擾」・「米暴動」「Kome-Sodo」「Kome-Sojou」「Kome-Bodo」

現在の学術用語となっている「米騒動」は、当時の新聞の紙面では、「米騒動」、「米騒擾」、「米暴動」という語句を中心に、いろいろな語句(歴史的語句)で表現されています。

吉河は大正7年米騒動を「所謂米騒動事件」として捉えました。「所謂米騒動」は、吉河が「哀願行動」と捉えた大正7年富山米騒動と騒擾罪や治安警察法違反が適用された全国的騒擾を合わせた概念です。吉河は検事の立場から、騒擾罪の適用された大都市の米騒動や治安警察法違反となった明治二坑労働争議を「米騒擾」として認識しました。すなわち、吉河は、刑事事件となり予審判事が公判起訴した騒擾や労働争議を「全国的騒擾」と認識しました。したがって、吉河は、富山米騒動では1人も起訴がなく、刑事事件になっていないため「米騒擾」と認識しませんでした。しかし、「米騒動」といえば富山に始まるというほど人口に膾炙しているため、富山米騒動を除外せずに、「所謂米騒動事件」として、富山米騒動も包含しました。

一方、『米騒動の研究』は街頭の騒動という民衆の行動形態を持つものを米騒動として認識しました。このことから、『米騒動の研究』は、大正7年米騒動の始まりを、女性荷役労働者が米の積み出しを阻止した大正7年富山米騒動としました。そして、大正7年米騒動の終わりを、9月12日に終息する万田坑の米騒動としました。治安警察法違反の明治二坑労働争議は街頭の民衆行動がないので米騒動としませんでした。

騒擾罪は、多数の民衆が集合し、共同意思をもって人や物を暴行し、公共の平穏を害する脅迫を行うことです。米騒動は騒擾罪として認識されており、内乱罪のように組織的な暴動集団が統治の基本秩序を壊乱するものではありません。当時の新聞記事には「米暴動」が多数使用されていますが、米騒動を「米暴動」と表現することは学術用語としては適切でないと考えます。

また、騒擾罪の「多衆」は数十名程度以上が集合することを構成要件とします。しかし、当HPは、山口県内の少人数や個人による米商の脅迫や米価引き下げの行動などを米騒動に含めています。また、前記の騒擾罪の構成要件に当てはまる場合は、「米騒動」を「米騒擾」と表現することもできると考えます。

騒擾罪を科した司法・治安当局の側の視点からみた場合は、米騒動は「米騒擾」・「騒擾」という認識が強いと考えます。一方、民衆側の視点からみた場合は、米廉売を求める生活防衛のための街頭の行動と捉えて、「米騒動」・「騒動」という認識が強いと考えます。すなわち、吉岡は「米騒擾」とし、『米騒動の研究』は「米騒動」としています。

大正7年米騒動は、街頭の騒動のあった「米騒動」、刑法の騒擾罪の適用された「米騒擾」の2つに分類できる。さらに、吉河は、治安警察法が適用された賃上げ要求の「労働争議」を米騒動として捉えていますので、米騒動には3つの形態があることになります。しかし、管理者は、労働争議は米騒動に含むべきでないと考えます。

The current academic term "rice riot (Kome-Sodo)" is expressed in various historical terms such as "Kome-sodo", "Kome-Sojou", and "Kome-Bodo" in the newspapers at that time.

Yoshikawa regarded the rice riots in 1918 as a "so-called rice riots incident." The "so-called rice riots" is a concept that combines the rice riots of Toyama in 1918, which Yoshikawa regarded as "the appeal movement," and the nationwide riots to which the crimes of disturbance and violations of the Security Police Act were applied. From the prosecutor's point of view, Yoshikawa recognized the rice riots in the big cities to which the crimes of disturbance were applied and the Meiji second coal pit labor dispute that violated the Security Police Law as "Kome-sojou." In other words, Yoshikawa recognized the riots and labor disputes that were prosecuted by the judge of preliminary trial in criminal cases as "nationwide riots." Therefore, Yoshikawa did not recognize it as a "Kome-sojou" because no one was charged in the Toyama rice riot and it was not a criminal case. However, it is well known that " the rice riots" started in Toyama, so Yoshioka included the Toyama rice riot in the nationwide riots and called it the "so-called rice riots incident."

On the other hand, "Study of the rice riots" recognized that the behavior of the people, the disturbance on the street, was the rice riot. For this reason, "Study of Rice Riots" marked the beginning of the rice riots of 1918 as the Toyama rice riots of 1918, when female cargo handling workers prevented the shipment of rice. The end of the rice riots of 1918 was marked as the rice riots of the Manda mine, which ended on September 12. "Study of rice riots" did not recognize the Meiji second coal pit labor dispute, which violated the Security Police Law, as a rice riot because there was no public action on the streets.

The crimes of disturbance are the gathering of a large number of people to jointly assault people and things, and threaten to harm public peace. The rice riots are perceived as the crimes of disturbance, and unlike the crime of insurrection that organized riot groups disrupt the basic order of governance. Many newspaper articles at that time used "Kome-Bodo," but I think it is not appropriate as an academic term to describe the rice riots as "Kome-Bodo."

In addition, the "many people" of the crimes of disturbance require crime-constituting condition that dozens or more people gather. However, this HP includes not only the actions of large number of people but also a small number of people and individuals in the rice riots, such as threats of rice merchants and actions to reduce rice prices. In addition, if the above crime-constituting condition for the crimes of disturbance are met, I think that "rice riots" can also be referred to as "Kome-Sojou."

From the perspective of the judicial and security authorities who have been guilty of the crimes of disturbance, I think that the rice riots are strongly recognized as "Kome-Sojo" and "Sojo." On the other hand, from the point of view of the people, I think that there is a strong recognition of "Kome-Sodo" and "Sodo" as a street action to defend the lives of people seeking a bargain sale of rice. In other words, Yoshioka refers to it as "Kome-Sojo," and "Study of rice riot" refers to it as "Kome-Sodo."

The rice riots of 1918 can be classified into two types: the "Kome-Sodo" where there was a street riot and the "Kome-Sojo" to which the crimes of disturbance of the criminal law were applied. Furthermore, Yoshikawa regards the "labor dispute" of the wage increase request to which the Security Police Law is applied as a rice riot, so there are three forms of the rice riot. However, Ibelieve that labor disputes should not be included in the rice riots.

《参考》「一揆」と「騒動」の違いの解説例<< Reference >> Explanation example of the difference between "Ikki" and "Sodo" 前掲『米騒動とジャーナリズム 大正の米騒動から百年』22~23頁 Above, "Rice riots and journalism: 100 years from the rice riots of the Taisho era," pp. 22-23

佐々木潤之助は幕末期から明治の初めにかけての封建社会解体期にあって、階級闘争の側面から次のように区別する。「『一揆』は、封建社会にとって基本である、領主対農民の間の基本的階級矛盾の激化したものとしての闘争であり、『騒動』は、人民の中に存在し、形成してくるところの、諸階層の間の矛盾の激化したものとしての闘争であって、その意味で、封建社会にあっては、副次的階級闘争である(佐々木潤之助『世直し』1979 岩波新書)。もちろん、「一揆」と「騒動」は、明確に分かれているものでなく、ケースによって混在するが、「打ちこわし」という行動に象徴される「騒動」は、下層都市民だけでなく、18世紀半ばからの商品経済の進行によって分解をはじめた農民層の中の下層農民を巻き込んで引き起こされるあらたな階級対立の場と理解できる。「騒動」の対立の場は、豪農・地主・有力商人対下層都市民・下層農民という図式である。「安政の大一揆」はまさに「一揆」であり、「騒動」でもあるという、大がかりな騒擾であった。」

Sasaki Junnosuke was in the period of dismantling the feudal society from the end of the Edo period to the beginning of the Meiji era, and distinguishes it as follows from the aspect of class struggle.”"Ikki" is a struggle as an intensified basic class contradiction between the lord and the peasant, which is fundamental to feudal society. On the other hand, "Sodo" is a struggle that exists and forms in the people as an intensified contradiction between the classes, and in that sense, in a feudal society, it is a secondary class struggle. (Sasaki Junnosuke "Yonaoshi" 1979 Iwanami Shinsho). Of course, "Ikki" and "Sodo" are not clearly separated and are mixed in some cases. The "Sodo" symbolized by the action of "Uchikowashi" can be understood as a place of class conflict that it is caused not only by the lower-level urban people but also by the lower-level farmers in the farmer group who have begun to decompose due to the progress of the commodity economy from the middle of the 18th century. The place of confrontation of "Sodo" is a scheme of a wealthy farmer, a landowner, a leading merchant vs. a lower-level city citizen, and a lower-level farmer. "Ansei Dai-Ikki" was a big Sojo , which was exactly a "Ikki" and a "Sodo". "

(3)近年の研究・新説 (3) Recent research and new theories

〇先行研究の出発点『米騒動の研究』 〇Starting point of previous research "Study of the rice riots"

井上清・渡部徹編『米騒動の研究』5巻は米騒動研究史における最大の業績です。

『米騒動の研究』5巻は1970年までにおける米騒動研究の到達点ですが、終着点ではなく出発点です。

井上・渡部は『米騒動の研究』第1巻の「はしがき」(1958年12月)で「この研究は、もとより完成したものではなく、むしろ今後の研究のために、しっかりした出発点をきずこうとするものである」と明確に述べています。

現在、『米騒動の研究』を深化する新たな研究が進められていますが、これらの研究を井上・渡部は期待していたと考えます。管理者も、『米騒動の研究』の業績の上に、宇部炭鉱と山口県を中心にして米騒動研究を深化させていきたいと考えます。

最近の研究では『米騒動の研究』に関して、井本三夫編『米騒動大戦後デモクラシー百周年論集Ⅰ・Ⅱ』(集広舎2019年)などにより、次のような批判や検討課題が出ています。

①これまでは米騒動の発生を社会運動発展の契機としてきたが、労働運動は米騒動以前にすでに高まっており、社会運動の高まりの結果として米騒動が発生したのではないか。

②米騒動を米価高騰による街頭の騒動として捉えるのではなく、米価高騰に伴う労働争議等を広く米騒動としてとらえるべきではないか。労働争議を含めた1階部分の上に、1918年米騒動という2階部分があると考えられないか。

③米騒動の期間を1918年7月22日(23日)から9月12日までとすることを検討する。労働運動の高まりを包摂して考えれば1917年からと考えられるし、富山県の米騒動に関しても東水橋町の女性荷役労働者の米の積み出し阻止の動きは1918年の7月上旬から始まっている。

④シベリア出兵と米価高騰、米騒動の連関に関する検討課題。シベリア出兵による米穀需要の増加は考えられない。なぜならシベリアに行かないで国内にいても米は食べる。また、出兵兵士の米消費量は国民全体からみれば需給関係や市場価格に影響を与える量ではない。しかし、これまで、シベリア出兵決定が米価のさらなる高騰を引き起こし、米騒動を激化させたとされてきた。

荻野喜弘『筑豊炭鉱労資関係史』(九州大学出版会1993年。200頁~215頁)では、1917年1月から1918年7月上旬までを「炭鉱労働争議」としている。一方、1918年8月17日から9月12日までを「筑豊における炭鉱米騒動」として分類している。荻野は、騒動は8月17日の峰地炭鉱から9月12日の三池炭鉱万田坑までに終息したとし、騒動をともなわない炭鉱労働争議は9月17日までとしている(荻野206頁)。荻野は米騒動9件と労働争議5件に分類し、1918年8月17日~9月17日の期間の労働争議を包摂して「いわゆる炭鉱米騒動」14件としている。荻野は、米騒動と労働争議を分類したうえで、両者を包摂して「筑豊における炭鉱米騒動」としている。

管理者は、宇部炭鉱の場合、1917年の沖ノ山炭鉱争議は労働争議であり、1918年の労働争議は大規模な米騒動に発展したと考える。また、軍隊の出動・発砲はシベリア出兵と連関していると考えている。このことから1918年宇部米騒動は炭鉱労働争議の性格だけではない他の性格を持っていると考える。

All five volumes of "Study of the Rice Riots" edited by Inoue Kiyoshi and Watanabe Toru are the greatest achievement in the history of rice riots research.

All five volumes of "Rice Riot Research" are the goal point of rice riot research by 1970, but they are not the end points but the starting points.

Inoue and Watanabe stated definitely in "Foreword" (December 1958), Volume 1 of "Study of the Rice Riot" that "This research was not completed, of course, but rather, this research is about building a solid starting point for future research. "

Currently, new research is underway to deepen the "Study of the Rice Riots," and I think Inoue and Watanabe were expecting these researches. The administrator also wants to deepen the rice riot research centering on the Ube coal mine and Yamaguchi prefecture, based on the achievements of "Study of the Rice Riots".

Recent research has raised the following criticisms and subject for future analysis to be examined in connection with "Study of the Rice Riots" by Imoto Mitsuo's edited "the Rice Riots / Postwar Democracy 100th Anniversary Collection I / II" (Shukousha 2019) and others.

(1) Until now, the occurrence of the rice riot has been regarded as an opportunity for the development of social movements, but the labor movement has already increased before the rice riots. Therefore, the rice riot may have occurred as a result of the rise of social movements.

(2) The rice riots should not only be regarded as a street riot caused by soaring rice prices, but should also be widely regarded as the rice riots, including labor disputes associated with soaring rice prices. Isn't it possible that there is a second-floor part called the 1918 rice riot above the first- floor part that include the labor dispute?

(3) Consider setting the period of the rice riot from July 22, 1918 (23rd) to September 12, 1918. Considering the rise of the labor movement, it is thought that it will be from 1917, and regarding the rice riots in Toyama Prefecture, the movement to prevent the shipment of rice by female cargo handling workers in Higashimizuhashi Town began in early July 1918.

(4) Issues to be examined regarding the link between Siberian intervention, rising rice prices, and rice riots. It is unlikely that the demand for rice will increase due to the Siberian intervention. Because soldiers eat rice even if they are in Japan without going to Siberia. In addition, the amount of rice consumed by troops is not the amount that affects the supply-demand relationship and market prices from the perspective of the entire nation. However, it has been said that the decision to send troops to Siberia caused a further rise in rice prices and intensified the rice riots.

In Ogino Yoshihiro's "History of Labor and Capital Relations in Chikuho Coal Mines" (Kyushu University Press 1993, pp. 200-215), the period from January 1917 to the beginning of July 1918 is referred to as the "the coal mine labor disputes", the other hand, from August 17th to September 12th, 1918, it is classified as "the coal mine rice riots in Chikuho". Ogino states that the riots ended from the Mineji Coal Mine on August 17th to the Miike Coal Mine Manda Pit on September 12th, and that the coal mine labor dispute without the riot was until September 17th (Ogino, p. 206). Ogino classifies the rice riots into 9 cases and labor disputes into 5 cases, and includes the labor disputes during the period from August 17 to September 17, 1918, to make 14 cases of "so-called coal mine rice riots". Ogino classifies the rice riots and labor disputes, and includes both as "coal mine rice riots in Chikuho."

In the case of the Ube Coal Mine, the administrator thinks that the 1917 Okinoyama Coal Mine dispute was a labor dispute, and the 1918 labor dispute developed into a large-scale rice riot. The administrator also thinks that the dispatch and firing of troops is linked to the Siberian intervention. From this, it is considered that the 1918 Ube rice riot has other natures than the nature of the coal mine labor dispute.

2022.1.11

〇米騒動の初期発生地・・東水橋町説・東部富山湾沿岸都市群説 The initial place of the rice riots ... Higashimizuhashi Town theory, Eastern Toyama Bay coastal city group theory

富山県米騒動の発祥地を魚津町とするのではなく東水橋町、西水橋町、滑川町、魚津町を含む東部富山湾沿岸都市を初期発生地とする研究があります。その中で、東水橋町では7月上旬から動きがあったという研究(東水橋町初期発生地説)がされています。また、魚津町の米騒動の発生日は7月23日にはじまるとされていますが、7月18日を発生日とする説や7月20日に米騒動が発生した新聞記事があり、発生日の検討がおこなわれています。

次は、井本三夫監修歴史教育者協議会編『図説 米騒動と民主主義の発展』(12~13ページ)からの引用(以下の《》内)です。全国の米騒動を研究したこの本では、富山県の東・西水橋町、滑川町の騒動に注目し、発祥についても7月上旬からの東水橋町の騒動を指摘しています。

There is a study that the origin of the rice riot in Toyama Prefecture is not Uozu Town, but the eastern Toyama Bay coastal cities including Higashimizuhashi Town, Nishimizuhashi Town, Namerikawa Town, and Uozu Town are the initial origins. Among them, there is a study (the theory of the initial occurrence of Higashimizuhashi Town) that there was a movement in Higashimizuhashi Town from the beginning of July. In addition, the date of the rice riot in Uozu Town is said to start on July 23, but there is a theory that the date of occurrence is July 18 and there is a newspaper article that the rice riot occurred on July 20. The day is being considered.

The following is a quotation (inside << >> below) from "Illustration: The Rice Riots and Development of Democracy" (pages 12-13) edited by the History Educator Council supervised by Imoto Mitsuo. This book, which studies rice riots nationwide, focuses on the Sodo in the eastern and western Mizuhashi towns and Namerikawa towns in Toyama prefecture, and points out the Sodo in Higashimizuhashi town from the beginning of July.

≪「漁村から始まった」は間違い:都市漁民であり多くは労働者の妻

富山湾沿岸に始まる18年後半の米騒動が漁民からであるのは、積出し状景を見せつけられていたことのほかにも理由がありました。保存のきかない「なまもの」を扱っていて、他の商売のように米価騰貴に対抗的な値上げができなかったからです。その場合、半農半漁なら米を買わずに済みますから、そのような漁民は米騒動を起こしません。だから米騒動を起こさざるを得なかったのは、背後を市街地で遮られた、当時でも人口1万から数千の、都市漁民(管理者註:周辺を商業地などの市街地で囲まれた都市部の漁民の町)たちだったのです。多くの通史・女性史の本が、富山県の「漁村」・「寒村」(管理者註:周辺を海と田畑と山林で囲まれた漁村を想像させる)から始まったと書いているのは、日本海側に対する先入観が生んだ、完全な間違いです。

また日本海側の産業革命は、東海側の政商財閥の汽船が入ってきて、北前船主たちから航路や荷を奪って北洋の漁業師などに追いやり、その乗組員たちを海運労働者や北洋労働者、港湾の荷役労働者などに組み込んでいく形で、陸上よりさきに海上で進行しました。ですから陸上での生活・習慣は旧態然と見えても、米騒動の女たちの多くは、(娘時代は自分も信州や大阪などの製糸・紡績の工女にいっていた)労働者の妻だったのです。そして日露戦後は幾つかの町で、彼女たち自身が荷役労働者になっていました。(管理者註:ここでいう「東海側」は日本海側に対して太平洋・瀬戸内海側(東京・大阪など)全体を指しており、東海地方という意味ではない)

勃発地は1つの町でなく、1つの地帯「東部富山湾沿岸都市群」

東部富山湾沿岸では、地主が小作から取り上げる米を、湾岸沿いの北陸街道にならぶ商人たちが、岸近くに汽船を呼びつけて艀で積み込み、北方植民地へ移出していました。それが、米を頭越しに積み出され、価格をつり上げられる都市漁民たちとの間に、一続きの階級対立地帯を作りあげました。ですから、複数の町で同時にまたは相次いで、他の町からの伝播ではなく自分の町のなかから、騒動が始まる町が幾つもあったのです。したがって1918年米騒動の勃発地は1つのまちではなく1つの地帯、東部富山湾沿岸都市群だったのです。どこか1つの町の騒動が、他のすべての町の騒動の源でもあることを意味する、発祥の地という言葉は使えません。

たとえば警察が多くを隠していたため、最初のように見えていた魚津町(現・市)での積出し停止要求を、発祥と呼び続けることはできません。女性荷役者(陸仲仕)の集団行動で、もっとも早く7月上旬から、しかも海岸だけでなく、移出商人の店や街道上の米車に対しても、より積極的な行動をとっていた東水橋町(現富山市内)の騒動はなぜそう呼ばれないのか、と問われるからです。また全国化の契機になったのは、東・西水橋町やもっとも激化した滑川町(現市)で、魚津ではなかったことも指摘されましょう。

富山県内での1か月の報道滞留を『高岡新報』が破る

7月上旬から始められていた東水橋町の米騒動で、移出商へ押しかけていた女性(陸)仲仕たちは、何度も私服巡査につきまとわれ、梅雨中で着ていた「ばんどり」(胴のない蓑・雨具)の下を検査されて、その下に背負っていた赤ん坊を泣かされたと語っています(「ばんどり」から7月上旬のの梅雨時であったことがわかる)。警察側はこうして知っていた東水橋町での米騒動の始まりを隠したまま、『北陸タイムス』・『富山日報』も魚津の7月20日からのこと、『北陸新報』は22日の富山での騒ぎについて書きながら、いずれも県外にそれらを発信することをしませんでした。この閉鎖性のため、7月上旬から富山県東部で起こっていた米騒動の情報は1月近くも県内に滞ったままだったのです。

ただ、県都の富山市でなく西部の高岡市にあって、県東部には手薄なはずの夕刊紙の高岡新報社だけが、通信員制度で知った西水橋町での米騒動の始まりを8月4日に掲載するとともに、同内容を『大阪朝日新聞』・『大阪毎日新聞』と石川県の2紙に電話しました。以後、『高岡新報』は東・西水橋・滑川の米騒動についての記事を連日掲載するとともに、それらを県外紙に送り続けます。それが8月5日から『大阪朝日新聞』・『大阪毎日新聞』などに「高岡電話」「高岡電報」として連日掲載されることによってその転載・抄訳と思われる記事が全国各紙に拡がっていったのです。≫

≪"Started from a fishing village" is wrong: Urban fishermen, often wives of workers

The rice riots in the latter half of 1918, which started on the coast of Toyama Bay, came from fishermen was not only because they were shown the shipment scenery. This is because they are dealing with "raw foods" that cannot be preserved, and they could not raise the price against the rising price of rice like other businesses. In half-farming and half-fishing case, such fishermen do not cause rice riots because they do not have to buy rice. Therefore, it was the urban fishermen who had no choice but to cause the rice riots, they lived in fishermen area where were blocked by the city behind them and had a population of 10,000 to thousands at that time. (Administrator's Note: A fisherman's town in an urban area surrounded by urban areas such as commercial areas) Many books on history and women's history write that the rice riots in Toyama Prefecture began in "fishing villages" and "poor villages." It is a complete mistake made by prejudice against the Sea of Japan side. (Administrator's Note: Imagine a fishing village surrounded by the sea, fields and forests)

In addition, the Industrial Revolution on the Sea of Japan side proceeded at sea before land, with the arrival of steamers from the political and commercial conglomerate on the Tokai side. They robbed the Kitamae shipowners of their routes and loads and sent them to North Sea fishermen etc. The crew were incorporated into shipping workers, North Sea workers, port cargo handling workers, and so on. In this way, the Industrial Revolution on the Sea of Japan side has progressed. Therefore, even though the life and customs on land seem old-fashioned, many of the women in the rice riots were the wives of workers. (When they were a daughter, they also went to Shinshu and Osaka, and worked as a female worker of silk-reeling or spinning-mill.) And after the Russo-Japanese War, in some towns, they themselves became cargo-handling workers. (Administrator's Note: The "Tokai side" here refers to the entire Pacific Ocean / Seto Inland Sea side (Tokyo, Osaka, etc.) with respect to the Sea of Japan side, and does not mean the Tokai region.)

The outbreak is not one town, but one zone "Eastern Toyama Bay coastal cities"

On the eastern coast of Toyama Bay, merchants along the Hokuriku-kaido along the bay called steamers to near the shore to load a barge the rice that took up by the landowner from the tenant farmers. And they were transporting it to the northern colonies. The price of rice bought by urban fishermen was raised by merchants. Also, merchants shipped rice without consulting fishermen. This created a series of class conflict zones along the eastern coast of Toyama Bay. So, in multiple towns at the same time or one after another, there were a number of towns where the Sodo began, rather than being propagated from other towns. Therefore, the outbreak of the rice riots in 1918 was not one town, but one zone, the eastern Toyama Bay coastal cities. The word birthplace which means that the Sodo in one town is also the source of the Sodo in all other towns cannot be used.

For example, because the police hid a lot, the request to stop shipping in Uozu Town (currently the city), which seemed to be the first, cannot continue to be called the birthplace. Why isn't Higashimizuhashi-cho, where there was a group action of female cargo handlers from the beginning of July at the earliest, called the birthplace? The female cargo handlers in Higashimizuhashi Town were positive actions not only on the beach, but also against on the shops of merchants handling rice exports and on carts carrying rice on the kaido. That is a question to be asked. It should also be pointed out that it was the eastern and western Mizuhashi towns and the most intensified Namerikawa town (current city) that triggered the Nationwide expansion, not Uozu.

"Takaoka Shinpo" breaks a month's unreported news in Toyama Prefecture

The female cargo handlers, who had been rushing to the transporters during the rice riots in Higashimizuhashi Town, which had begun in early July, were tailed repeatedly by police officers in plain clothes. And the women say that they were inspected by a police officer the inside of the "bandori" (a torsoless mino) that they wore in the rainy season, and the baby the inside of "bandori" was made to cry. The police remained hiding the beginning of the rice riot in Higashimizuhashi, which they knew. In addition, "Hokuriku Times" and "Toyama Daily" write about the uproar from July 20th in Uozu, and "Hokuriku Shinpo" write about the uproar that occurred in Toyama on the 22nd. However, none of the newspapers disseminated those uproars outside the prefecture. Due to this closure, information on the rice riots that had occurred in the eastern part of Toyama Prefecture since early July remained in the prefecture for nearly January and was not transmitted outside the prefecture.

The evening newspaper Takaoka Shinpo was not in Toyama City of the capital of the prefecture, but in Takaoka City in the western part of the prefecture, and information on the eastern part of the prefecture was scarce. However, only Takaoka Shinpo reported on August 4 the beginning of the rice riot in Nishimizuhashi, which was informed by the correspondent system. In addition, Takaoka Shinpo called the same content to "Osaka Asahi Shimbun" and "Osaka Mainichi Shimbun", and two newspapers of Ishikawa Prefecture. Since then, "Takaoka Shinpo" published articles about the rice riots in Higashi / Nishimizuhashi Town and Namerikawa Town every day, and continued to send them to newspapers outside the prefecture. From August 5th, it was published daily as "Takaoka Telephone" and "Takaoka Telegram" in "Osaka Asahi Shimbun" and "Osaka Mainichi Shimbun". Then, the articles that seemed to be reprints and abstracts spread to various newspapers nationwide. ≫

〇魚津町の発生日(7月23日)についても異説あり 〇 There is also a disagreement about the date of occurrence of Uozu Town (July 23).

魚津町における発生日について、米騒動史研究会北陸支部は、魚津は7月18日から米騒動がはじまったという問題提起をしています(『歴史評論』(459)「米騒動の日付修正と『米騒動の研究』・『細川資料』の限界」)。これに対し、紙谷信雄は、魚津は7月18日からはじまるという説に反論しています(『歴史評論』(472)「「魚津は七月十八日から」説を疑う」)。

Regarding the date of occurrence in Uozu Town, the Hokuriku Branch of the Rice Riots History Study Group has raised the issue that Uozu started the rice riot from July 18 ("Historical Journal" (459). "Revision of the date of the rice riot, "Study of the Rice Riot" and "Limitations of Hosokawa Documents"").In response, Kamitani Nobuo argues against the theory that Uozu will start on July 18 ("Historical Journal" (472) "I doubt the theory that" Uozu will start on July 18 ").

7月20日の魚津町の騒動を伝える『北陸タイムス』7月24日・25日付の記事。An article dated July 24th and 25th in "Hokuriku Times" that conveys the disturbance in Uozu Town on July 20th.

この記事は、前記の『図説 米騒動と民主主義の発展』が指摘している魚津町の7月20日の騒動を『北陸タイムス』が報道した記事です。7月20日に魚津町で米騒動が発生したことを示す記事であり、富山米騒動(魚津米騒動)が7月23日に始まるという通説を覆す内容となっています。

(『北陸タイムス』7月24日の記事表題に職業差別用語2字が記載されているので管理者が塗りつぶしています。当時の新聞には人権侵害や差別的用語に当たる語句や記事が多数記載されています。24日・25日の米騒動以外の記事を塗りつぶしていますが、その中にも人権侵害の記載があります。)

This article is an article reported by the "Hokuriku Times" on the July 20th disturbance in Uozu Town, which was pointed out in the above-mentioned "Illustration: Rice riots and the development of democracy." This article shows that the rice riot occurred in Uozu Town on July 20, and it overturns the conventional wisdom that the Toyama rice riot (Uozu rice riot) will start on July 23.

(The article title of "Hokuriku Times" on July 24th contains two characters of occupational discrimination terms, so the administrator fills them in. Newspapers at that time contained many words and articles that corresponded to human rights violations and discriminatory terms. I have filled in articles other than the rice riots on the 24th and 25th, but there is also a description of human rights violations in it. )

〇人権を考慮した記述 〇 Description considering human rights

井上清・渡部徹編『米騒動の研究』(全5巻)では刑罰を科された人物の姓名や本籍地(番地)などの個人情報が記載されています。当HPではこれらの個人情報を記載していません。

部落とは、村内の共同体であり、現在の自治会にあたる地縁団体のことで、日本の村〈大字・おおあざ〉は部落(小字・こあざ・小名)という地域集落の集合体でできています。部落は一般的な語句で差別用語ではありませんので、当HPでは史料にでてくる「部落」、「部落民」はそのまま使用しています。ただし、部落のなかには差別を受けた部落があり、この部落を差別意識を含んで「部落」とよんだり、あるいは差別をうけている「部落」の意味で、学術的に「被差別部落」、「未解放部落」とよんでいます。また、行政史料や新聞などは、差別を受けた「部落」を、差別的表現で「特種部落」・「特殊部落」と記載しています。たとえば、『米騒動の研究』は、「特種部落民」という差別用語や被差別部落名などを史料・新聞の記載のまま記述しています。『米騒動の研究』は、人権感覚に問題点があり、この本の差別的な記述を引用すると人権侵害に当たります。山口県では、人権課題解決のための粘り強い施策を推進していますが、「被差別部落」の差別的表現が史料のまま引用されたため、2018年3月に『山口県史 通史編 近代』が回収され、訂正後に再配布されるという事態が生じました(クリック・内部リンク)。

当HPでは、「被差別部落」の記述は、人権問題、同和問題の一般的な基準に適合した記載をしています。

Inoue Kiyoshi and Watanabe Toru editing "Study of the Rice Riots" (5 volumes in total) contains personal information such as the surname and registered domicile (address) of the person who was punished. This HP does not list these personal informations.

Buraku is a community within the village, which is the current community association, and Japanese villages(O-aza) are made up of a collection of local communitiest(Ko-aza) called Buraku. Buraku is a general term and not a discriminatory term, so in this HP, "Buraku" and "Burakumin" that appear in historical materials are used as they are. However, some Buraku have been discriminated against, and this Buraku is called a "Buraku" with a sense of discrimination. In addition, the "Buraku" who are discriminated against are academically called "Hisabetsu-Buraku" and "Mikaiho-Buraku".In addition, in administrative historical materials and newspapers, discriminated "Buraku" are described as "Tokushu-Buraku" and "Tokushu-Buraku" in discriminatory terms. For example, "Study of the Rice Riots" describes such as the discriminatory term "Tokushu-Burakumin" and the names of Hisabetsu-Buraku as they are written in historical materials and newspapers. "Study of the Rice Riots" has a problem with the sense of human rights, and quoting the discriminatory description of this book is a violation of human rights. Yamaguchi Prefecture is promoting tenacious measures to resolve human rights issues. However, because "Yamaguchi Prefecture History, Complete History Edition, Modern" quoted the discriminatory expression of "Hisabetsu-Buraku" as historical materials, it was collected in March 2018 and redistributed after correction (click/ Internal link).

On this website, the description of "Hisabetsu-Buraku" conforms to the general standards of human rights and Dowa issues.

〇米騒動の論点の1例 〇 An example of the issue of the rice riots

『詳説日本史B』(山川出版社。平成19年度版)は、「社会運動の勃興と普選運動」の項目で、「ロシア革命・米騒動などをきっかけとして、社会運動が勃興した」と記載している。このように、米騒動に民衆が参加し、その行動を体験した後に、労働運動などの社会運動が急速に発展したというのが定説でした。しかし、米価高騰による労働争議が頻発したのは米騒動の前年からというのが事実です。

米騒動は、米価高騰により発生した勤労者による街頭の大衆行動で、その後の組織的な社会運動高揚の契機となったとして捉える説があります。(井上清・渡部徹編『米騒動の研究』)また、社会運動高揚の契機ではなく、全階級の市民が参加した組織的な民衆運動(あるいは民衆蜂起)として捉える議論があります。

大戦景気により米価が高騰し、賃上げ要求の労働争議が急増する1917年(大正6)と米騒動の関連を検討する動きがあります。(米騒動・大戦後デモクラシー百周年研究会(クリック・外部リンク))。労働争議は1917年から急増したと指摘されている。『米騒動の研究』が主張している1918年の米騒動を契機に労働運動が高まったという認識は、以下の斉藤論文で説明されるように批判されています。

最近は米騒動への関心が低調になったという指摘もあります。しかし、米騒動の発生日、米騒動の概念、米騒動の歴史的な位置と意義などを論点に、現在も活発な研究・議論が続いています。米騒動は近代史の転換点に位置する重要な歴史的事象です。米騒動100年を契機に関心が高まり、研究・教育が活発化することを期待しています。

《関連》斉藤正美「口述史料が映す米騒動の女性労働者」『歴史評論』(776)2014.12 76~88頁

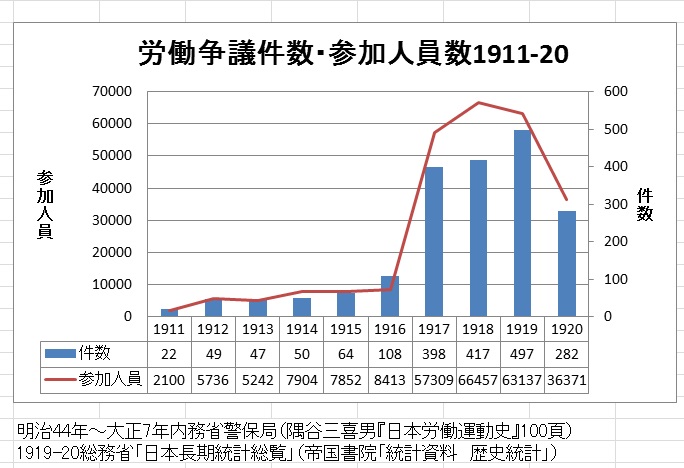

斉藤は、「米騒動は自然発生的な哀願運動」でその後の「社会運動・階級闘争のいっせい発展の跳躍台」となったとする『米騒動の研究』を批判的に検討している。「一九一八年の「米騒動」はまぎれもなく民衆運動であった。無産階級の女性でもあり、労働者でもあった女性たちの「生活権」を求めての民衆運動であった、とみるべきであろう」(鈴木裕子編『日本女性運動資料集成 第四巻 生活・労働Ⅰ 女性労働者の組織化』1994 32頁)(富山県の漁民「女房」たちには仲仕などで賃金を得る労働者が多かったと言う)。「まさに日本全国を揺るがす民衆の蜂起」(石月静恵『近代日本女性史講義』2007。86頁)という米騒動の評価を紹介している。そして、『米騒動の研究』が米騒動を「次なる社会運動を準備する「跳躍台」にすぎない」、と限定的に見ていることを批判している。また、『米騒動の研究』の井上清が、米騒動後の1919年ごろから労働運動が急速に発展したとしていることに対し、次のグラフからもわかるように、1917年から発展しておりり、誤りであることを指摘している。

《関連》井本三夫『米騒動という大正デモクラシーの市民戦線 始まりは富山県でなかった』(2018年12月 株式会社現代思潮新社)

近年の米騒動研究を先導してきた井本三夫の集大成ともいえる近著である。

日本近代の米騒動を(2+1)重構造として、2(A勤労者による賃上げ騒擾。B居住区消費者運動)+1(C植民地・従属地域の運動)に分類した。

さらに、それを近世以来のa賃上げ型、b街頭型(b1歴史的特徴の濃い区域の街頭型 b2米産地の津止め(移出反対)街頭型)に分類した。34頁。

その上で、大正7年(1918)富山米騒動は街頭型b2に分類した。賃上げ騒擾・暴動(A+a)と居住区消費者運動(B+b1)は大正6年(1917)から始まっている。したがって、街頭型米騒動のみに注目して富山県を嚆矢としている『米騒動の研究』を批判している。

また、井本は、米騒動は、「全ての民主主義運動・文化運動の扉を開き、またそれによって組織的労働者階級とその政党への途を拓いた」としている。すなわち「大正デモクラシー」を新しい段階に止揚した「かけがえのない市民戦線」と位置づけている。39頁。

米騒動の性格を広く捉え、国内だけでなく、東南アジア・中国・朝鮮・台湾、さらには欧州市場まで俯瞰して米騒動を分析しようとする労作である。

"Detailed Japanese History B" (Yamakawa Shuppansha, 2007 edition) states that "social movements have risen in the wake of the Russian Revolution and the rice riots" in the item "Social movements have risen and the general election movement". In this way, it was the established theory that social movements such as the labor movement developed rapidly after the people participated in the rice riots and experienced their behavior. However, the fact is that labor disputes due to soaring rice prices began to occur frequently the year before the rice riots.

There is a theory that the rice riots are a mass action on the streets by workers caused by soaring rice prices, and it is regarded as an opportunity for the subsequent systematic social movement to rise. (Inoue Kiyoshi and Watanabe Touru, "Study of the Rice Riots") In addition, there is a debate that it is not an opportunity to raise social movements, but a systematic popular movement (or popular uprising) in which citizens of all classes participate.

There is a movement to consider the relationship between the rice riots and 1917 (Taisho 6) when rice prices soared due to the War Boom and labor disputes for wage increases surged. (Rice riots, Post World War 1 democracy 100th anniversary study group (click, external link))

It has been pointed out that labor disputes have skyrocketed since 1917. The recognition that the rice riots of 1918, which "Study of the rice riots" insisted, increased the labor movement, has been criticized as explained in the following Saito paper.

It has been pointed out that interest in the rice riots has recently declined. However, active research and discussions are still ongoing, focusing on the date of the rice riot, the concept of the rice riot, and the historical position and significance of the rice riots. The rice riots are an important historical event at a turning point in modern history.

I hope that the 100th anniversary of the rice riots will raise interest and stimulate research and education.

<< Related >> Saito Masami , "Female Workers in the Rice Riot Reflected by Oral Historical Materials," "Historical Journal," (776) 2014.12, pp. 76-88.

Saito is critically examining the "Study of the Rice Riots", which states that "the rice riots is a spontaneous the appeal movement" and later became a "jumping platform for the simultaneous development of social movements and class struggles." "The 1918" rice riots " was undoubtedly a people movement. It should be seen that it was a people movement for the "right to life" of women who were both proletariat women and workers. " (Suzuki Yuko editing, "Collection of Japanese Women's Movement Materials, Volume 4, Life and Labor I, Organization of Female Workers," 1994, p. 32) (It is said that many of Toyama Prefecture's fishermen "wife" earned wages through cargo handlers (Nakashi), etc.). Saito introduces that the evaluation of the rice riots, "Exactly the uprising of the people who shakes the whole of Japan" (Ishizuki Shizue, "Lecture on Modern Japanese Women's History", 2007, p. 86). He criticizes the "Study of the Rice Riots" for its limited view of the rice riots as "just a" jumping platform "to prepare for the next social movement." In addition, Inoue Kiyoshi of "Study of the Rice Riots" states that the labor movement has developed rapidly since around 1919 after the rice riots, but as can be seen from the following graph, it has been developing since 1917. Therefore, Saito points out that Inoue's idea is an error.

<< Related >> Imoto Mitsuo "Citizen's Front of Taisho Democracy called Rice Riots: The beginning was not in Toyama Prefecture"(December 2018, Gendaishicho-sinsha Co., Ltd.)

This is a recent book that can be said to be the culmination of Imoto Mitsuo, who has led the study of rice riots in recent years.

The rice riots of modern Japan were classified into 2 (A riot of wage increases by workers; B residential area consumer movement) +1 (C colonial / subordinate area movement) as a (2 + 1) Stacking structure.

Furthermore, Since the early modern period, he classified into (a) wage increase type and (b) street-type ((b1) street-type in areas with strong historical characteristics, (b2) Stop at the port (oppose to transport to another area) street-type in rice production areas). Page 34.

On that basis, the Toyama rice riots of 1918 were classified as street type b2. The wage increase riots and riots (A + a) and the residential area consumer movement (B + b1) began in 1917. Therefore, he criticizes the "Study of the Rice Riots", which focuses only on the street-type rice riots and has Toyama Prefecture as its starting point.

In addition, Imoto said that the rice riot "opened the door to all democratic and cultural movements, and thereby paved the way for the organized working class and its political parties." In other words, it positions "Taisho Democracy" as an "irreplaceable civil front" that has sublated a new step. Page 39.

It is an effort to broadly grasp the nature of the rice riots and analyze the rice riots from a bird's-eye view not only in Japan but also in Southeast Asia, China, Korea, Taiwan, and even the European market.

2022.1.12

《参考資料》労働争議件数の推移(1917年「ストライキ運動飛躍の年」) )<< Reference >> Changes in the number of labor disputes (1917 is "the year when the strike movement made a leap")

大戦景気による物価上昇に賃金上昇が伴わなかったため、1917年に労働争議が急増した。このことは、1917年から広義の米騒動(対米価賃上げ争議)が始まったという説の根拠になっている。井本三夫は、「日本近代米騒動の複合性と朝鮮・中国における運動」『歴史評論』(四五九)1988年、17頁で、「米価騰貴に対する賃上げ争議である限り、それは近代米騒動の一部を成すと云わねばならない」としている。

Labor disputes surged in 1917 because wages did not rise despite rising prices due to the War Boom. This is the basis of the theory that the rice riots in a broad sense (labor disputes over wage increases against soaring rice prices) began in 1917. In "The Complexity of the Modern Rice Riots of Japan and the Movement in Korea and China", "Historical Journal" (459), p. 17, 1988, Imoto Mitsuo wrote that "As long as there is a wage increase labor disputes against rising rice prices, it must be said that it forms part of the rice riots of modern times."

(4)米騒動の報道 (4) Report on the rice riots

西水橋町の米騒動(8月3日)を伝えた『高岡新報』(8月4日付)と『大阪朝日新聞』(8月5日付)の記事 Articles of "Takaoka Shinpo" (August 4th) and "Osaka Asahi Shimbun" (August 5th) that reported the rice riot in Nishimizuhashi Town (August 3rd)

富山の米騒動を『大阪朝日新聞』(『大朝』)や『大阪毎日新聞』(『大毎』)などに伝えたのは、『高岡新報』記者の井上江花(こうか)です。井上江花の打電(高岡電報・高岡電話)により、8月5日以降、全国紙が連日報道し、越中(富山)の「女房一揆」、「女一揆」が全国に伝わりました。

It was Inoue Kouka, a reporter of "Takaoka Shinpo", who reported the rice riots in Toyama to "Osaka Asahi Shimbun" ("Daicho") and "Osaka Mainichi Shimbun" ("Daimai") and others. Inoue Koka's telegram (Takaoka Telegram, Takaoka Telephone) has been reported every day by national newspapers since August 5, and Ettchu (Toyama)'s "Nyobou (Wives) Ikki" and "Onna (Women) Ikki" have been transmitted nationwide.

大正時代は新聞や雑誌などのマスメディアが発達した時代です。当時の新聞は、非立憲的性格の寺内内閣倒閣運動を展開しており、シベリア出兵にも反対していました(出兵開始後は協調)。政府は米騒動の拡大や関東への伝播(東京市の米騒動が13日からはじまる)に(倒閣の政治的意図のある)新聞報道が影響しているとみていました。8月14日深夜、水野錬太郎内務大臣は「米価に関する各地騒擾に関係ある記事、及び大阪の騒擾に関する号外を発行することの二項を禁止」(『大阪朝日新聞』大正7年8月15日)することを新聞・雑誌に伝え、米騒動報道は禁止された。新聞社の抗議により、16日から、内務省の公報(日に2回)を基調とする事実の記載は認められた。その後、言論報道の自由の抗議により、内務省は18日から公報を5回発表し、誇張煽動的でない場合、米問題に関する騒擾記事の掲載を解禁した。

The Taisho era was a time when mass media such as newspapers and magazines developed. The newspapers at that time were developing a movement to overthrow the Terauchi Cabinet, which had an unconstitutional character, and also opposed the Siberian intervention (cooperation after the start of the dispatch). The government believed that the spread of the rice riots and its spread to the Kanto region (the rice riot in Tokyo began on the 13th) was affected by newspaper reports with the political intention of the collapse of the cabinet. At midnight on August 14, Minister of Interior Mizuno Rentaro informed newspapers and magazines that "the two matters of issuing articles related to the riots in various places regarding rice prices and extra edition related to the riots in Osaka are prohibited." ("Osaka Asahi Shimbun" August 15, 1918). For this reason, reporting on the rice riots was prohibited. Due to the protest of the newspaper company, it was allowed to write the facts based on the Ministry of Interior's bulletin (twice a day) in the newspaper from the 16th. After that, in response to a protest for freedom of the press, the Ministry of Interior published five bulletins from the 18th, and lifted the ban on the publication of riot articles on the rice riots if it was not exaggerated.

歴史探偵『米騒動』NHK総合2020.8.31放送(作成中)

2022.9.5更新

映画「大(だい)コメ騒動」全国公開2021.1.8 Movie " Big Rice Riot" released nationwide 2021.1.8

本木克英監督。

井上真央、室井滋、夏木マリら出演。

富山米騒動の史実に基づく痛快エンタテインメント!

山口県内ではイオンシネマ防府(防府駅前)で上映されているのでコロナ対策をして鑑賞を楽しみにしています。

2021.1.10

Director Motoki Katsuhide

Performed by Inoue Mao, Muroi Shigeru, Natsuki Mari and others.

Exciting entertainment based on the historical facts of the Toyama rice riot!

In Yamaguchi Prefecture, it is being screened at Aeon Cinema Hofu (in front of Hofu Station), so I am looking forward to seeing it with corona measures.

2021.1.10

本日(2021.1.13)イオンシネマ防府に行ってきました。いい映画でしたので多くの方に鑑賞していただきたいですね。

主題歌は米米CLUB(こめこめくらぶ)の「愛を米(こめ)て」、なるほど。

山口県内にシネコンが4館ありますが上映は当館のみ。イオンもなかなかやりますね。

映画鑑賞後、防府天満宮にお参りし、遅れた初詣をしました。参道にある大専坊(だいせんぼう)には幕末、遊撃軍(来島又兵衛(きじま-またべえ)総督)の屯所がありました。その後、英雲荘(三田尻御茶屋((みたじりおちゃや)を見学して館員の方から詳しく説明していただきました。最後に桑山(くわのやま)に登り、幕末に戦没した御盾隊(みたてたい)隊士らの招魂碑に手を合わせました。桑山の麓にある大楽寺(だいらくじ)は楫取素彦(かとりもとひこ)夫妻の墓所で、妻はNHK大河ドラマ『花燃ゆ』で井上真央の演じた文(ふみ。吉田松陰の妹))です。この寺に女優の夏目雅子のお墓があったのにはびっくりしました。

「大コメ騒動」のお陰で、楽しく充実した1日となりました。

2021.1.13

I went to Aeon Cinema Hofu today (2021.1.13). It was a good movie, so I hope many people will watch it.

The theme song is "Put love in rice (Kome)" by Kome Kome Club, I see.

There are 4 cinemas in Yamaguchi prefecture, but only this one is screened. Aeon also does pretty good things.

After watching the movie, I visited Hofu Tenmangu Shrine and had a first visit after the New Year. At the end of the Tokugawa shogunate, there was a military post of the "Yuugekigun", which was governed by Kijima Matabei, at the Daisenbo next to the stone steps on the approach to the shrine. After that, I visited Eiunso, the site of the Mitajiri Ochaya, and the staff explained it in detail. Finally, I climbed Kuwanoyama and visited the monument to the souls of the Mitate-Tai's soldiers who died at the end of the Tokugawa shogunate, and I prayed. Dairakuji at the foot of Kuwanoyama is the graveyard of Mr. and Mrs. Katori Motohiko, and his wife is Fumi (sister of Yoshida shoin) played by Inoue Mao in the NHK Taiga drama "Hana Moyu"). I was surprised that there was a grave of actress Natsume Masako in this temple.

Thanks to the "Big Rice Riot", it was a fun and fulfilling day.

2021.1.13

2024.11.11更新 2024.11.11update